Workforce Blurred: Flexibility, Motivation, and Trust Reinforce One Another in Hybrid Work Environments

Corgan’s report, Workforce Blurred, uncovered numerous insights on what freshly minted graduates and seasoned professionals looking for their next step are looking for from the future of work. The study combined quantitative data from more than 150 surveys and qualitative data from in-depth interviews with graduates across the nation and those making a career change to understand the preferences, needs, and expectations of the emerging workforce. Marked by a historic global pandemic accompanied by an economic downturn with high unemployment, those entering today’s workforce have been forced to quickly adapt to changing landscapes while wrestling with career anxieties. It is a ripe opportunity for architects and designers to respond with an empathetic, human-centric design that thoughtfully supports this incoming generation of workers.

While students are enrolled in school, they adopt flexible working strategies — they build their own schedules, decide how much work to contribute for each of their classes, and learn how to ask for help through arrangements like office hours and tutoring centers. This promotes the use of skills like effective time management, asynchronous and synchronous learning styles, clear communication, and project management. Their desire for autonomy and flexibility in a future workplace seems to emerge as a natural extension of their student experience. This generation has also grown up in an era of personal data tracking. As a result, they may be accepting constant monitoring in exchange for more freedom, autonomy, and flexibility.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has also forced workplace flexibility into the spotlight and is now perceived as an expected benefit of a job offer. The reason workplace flexibility is so valuable to people can be found in its relationship to time. Years of social science research tell us that people are motivated by their own autonomy. Autonomy motivates the unconscious part of the brain — making us feel in control by minimizing the likelihood of danger. Additionally, people are more influenced by time and experience rather than money or possessions.

Flexibility is Not an Amenity, it is Part of Workplace Culture

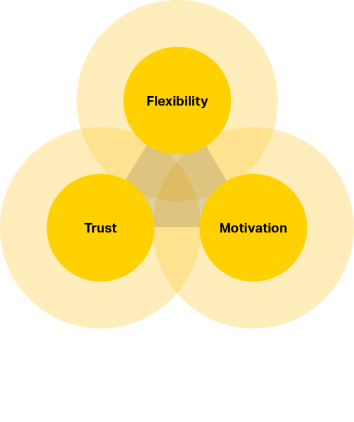

The recent graduates we spoke with are new to the workforce and want to prove that they can complete work on their own while still feeling supported by their managers. Throughout our interview sessions, participants expressed frustration with micromanagement techniques which, in turn, discourage intrinsic motivation and drive. This desire for autonomy requires an environment that facilitates trust, which then encourages flexibility and, in turn, reinforces motivation. More established workers also appreciate flexibility. It provides them with time to focus on their tasks off-site (encumbered by common workplace distractions) but still values being in the office together with their team for valuable face-to-face time. When these seasoned work professionals are given flexibility, they feel appreciated and more balanced, which allows them to focus on their work with more intention and purpose. Flexibility, motivation, and trust have a relationship with one another in remote settings.

The majority of interview participants preferred a hybrid work option, even if they would work remotely the majority of the time, they appreciated having the flexibility and option to go into the office when it was beneficial to their needs. These qualitative reports supported our quantitative survey findings such that 92% of respondents selected a hybrid work arrangement. None of the survey participants chose a fully remote option. Although some employees still want to have the option to go in every day, others view it as one tool in their job toolkit stating that going in five days a week isn’t necessary anymore and that cutting back on driving would be suitable for them the environment.

Types of Motivation

There are many reasons why people work (it’s not just about money). Academics have studied why people work for nearly a century, but in the 1980s, Edward Deci and Richard Ryan from the University of Rochester identified the six key motivations behind work. Additional research has also found that the first three motives listed tend to increase performance, while the latter impedes.

- Play is when you are motivated by the work itself. You work because you enjoy it. Play is our learning instinct, and it’s tied to curiosity, experimentation, and exploring challenging problems.

- Purpose is when the outcome of work fits your identity. You work because you value the work’s impact.

- Potential is when the outcome of the work enhances your identity or opportunity for growth and advancement. In other words, the work enhances your potential.

- Emotional pressure is related to an external force that threatens your identity. If you’ve ever used guilt to compel someone to do something, you’ve inflicted emotional pressure.

- Economic pressure is when an external force makes you work. You work to gain financial reward or avoid punishment. This motive is separate from the work itself as well as separate from your identity.

- Inertia is when the motive is removed from both work and identity that you can’t identify why you’re working. When you ask someone why they are doing their work, they say, “I don’t know; I’m doing it because I did it yesterday and the day before,” which signals inertia. It is still a motive because you’re still actually doing the activity; you just can’t explain why.

Impact on the Workplace

As the world becomes more interconnected and complex, it’s important to consider the different ways in which people are interacting with and perceiving the built environment. The future of work extends beyond the physical footprint of the office. Younger generations are accustomed to living in a digital world, which they access from physical spaces— but today, the ecosystem of work is both digital and physical, and flexibility is an expectation, not a preference.

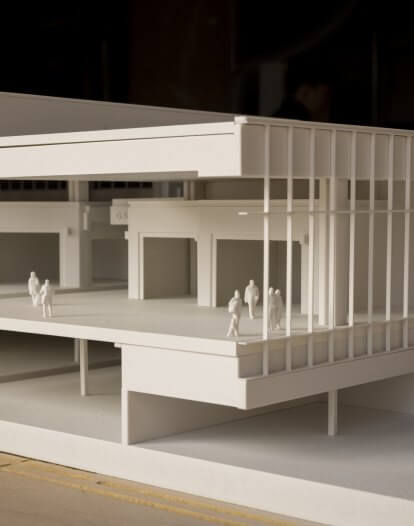

User experience within the building context should be considered from the time they park. From the entrance to the configuration of individual spaces, the overall facility should support flexibility and ease. Social interaction should be enhanced by increasing opportunities for both spontaneous and planned engagement. To enable flexibility, consistent and seamless technology must be implemented. When designing for technology, think outside of the building and to the entire ecosystem.

Personal ownership of space is a tradeoff for the freedom of flexibility. Social spaces should be prioritized, while enclosed spaces will provide flexibility, heads-down space, and effective hybrid collaboration. Unassigned seating sends a message that your location does not define your productivity. You are trusted to accomplish your work regardless of being seen.

Learn more about the insights and what it means for the office in the full report: Workforce Blurred.

Corgan’s Workforce Blurred report is part of an ongoing investigation of the future of work. From how to tackle and incorporate new technologies to what lifestyle shifts and demands of a changing workforce mean for the office, Corgan’s research explores the most pressing questions facing the workplace. Take a look at our previous report Work. Place. Blurred.—a study on how an increasingly mobile, fluid, and connected world is responding to the challenges and benefits of remote work to learn more about how our insights are shaping the future of work.

TheSquare Ep 05 · The Psychology of Trust

Workplace expectations have changed. COVID-19 has dramatically shifted how we come to work and what we need from the office. Where glossy amenities including local kombucha and ping pong tables took center stage in the war on talent, the global pandemic has highlighted what we may have taken for granted in human-centric design: trust. Fundamental to any relationship, trust between staff, colleagues, and employers raise new priorities including boundaries, transparent two-way communication, and accountability that are at the core of what we need to not only feel safe at work but confident about returning to the office. In this episode of TheSquare Jacquelyn Hunter, Project Design Manager at Corgan, and Jane Hensley, MRC, CRC, LPC specializing in culture and crisis management, explore the psychology of trust—the pillars of how design, both seen and unseen, shapes our confidence in the built environment and in those we work with. From material finishes to communication best practices, the return to the office and to a renewed confidence in the workplace depends on an experience founded on a series of small moments and empathetic design that responds to the vulnerabilities, mindsets, stressors, and needs of staff. Stay tuned as we continue to probe further into the power of design to build trust in these uncertain and unprecedented times.