Focus by Design — What the ADHD brain teaches us about better workspaces for all

What if focus isn’t just a skill, but a setting?

While some thrive in the buzz of an open office, others find that the same energy divides attention and drains mental stamina. For individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), those environmental factors aren’t minor distractions — they can define whether work feels possible or impossible on a given day.

That reality led Hugo, Corgan’s Research and Innovation team, in partnership with the University of Arkansas, to launch a study through the AIA Upjohn Research Initiative to better understand in-office attention by relating people’s lived experience with measurable data on how the brain and environment interact. a population whose focus is acutely shaped by its surroundings — with the aim to reveal what design strategies help all of us find and sustain attention.

Why ADHD and How it Shows Up at Work

Neurodiversity represents countless ways of experiencing the world. Each condition within that spectrum has its own distinct rhythm, reflecting how people think, learn and process the world.

Among them, inattentive-type ADHD offers a unique lens for understanding how the environment shapes focus. It is estimated that about 15.5 million U.S. adults live with ADHD, though that number continues to rise as awareness grows and diagnostic criteria evolve.1 Even with this increase, the condition remains underrepresented, particularly among women and minority groups.2

The inattentive type ADHD is characterized by difficulty sustaining focus, staying organized and managing time.3 People may find it challenging to follow a sequence of tasks, filter distractions, or maintain motivation through routine work, particularly in workplace settings traditional to knowledge work, desk-based environments that offer little variety and require prolonged, sedentary focus.3 These challenges often collide with the sensory complexity of most modern workplaces, where bright lighting, background noise, and constant movement can easily pull attention away, while overly quiet or monotonous settings make it harder to stay engaged.4 Because the same environment that supports one person’s focus may overstimulate another, understanding how different individuals respond to light, sound, movement, and visibility provides valuable insight for designing spaces that accommodate a broader range of needs and sustain focus for everyone.

Measuring the Connection Between Brain and Environment

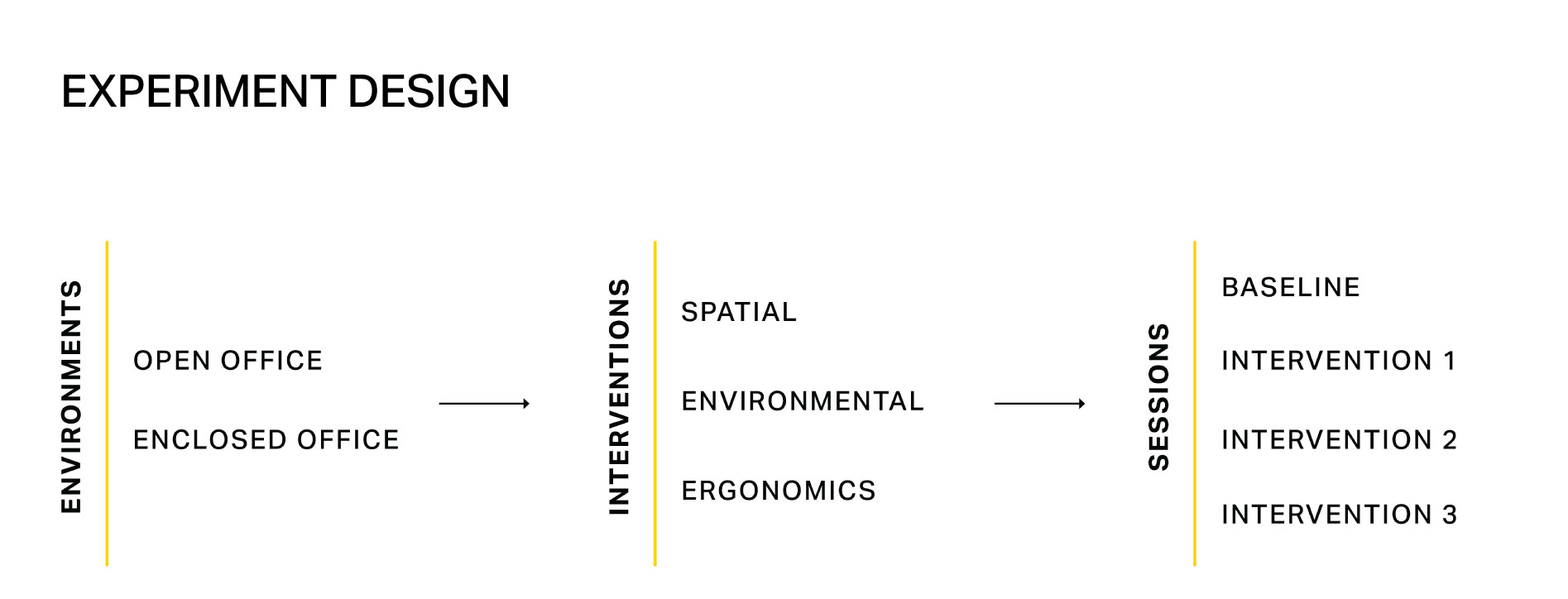

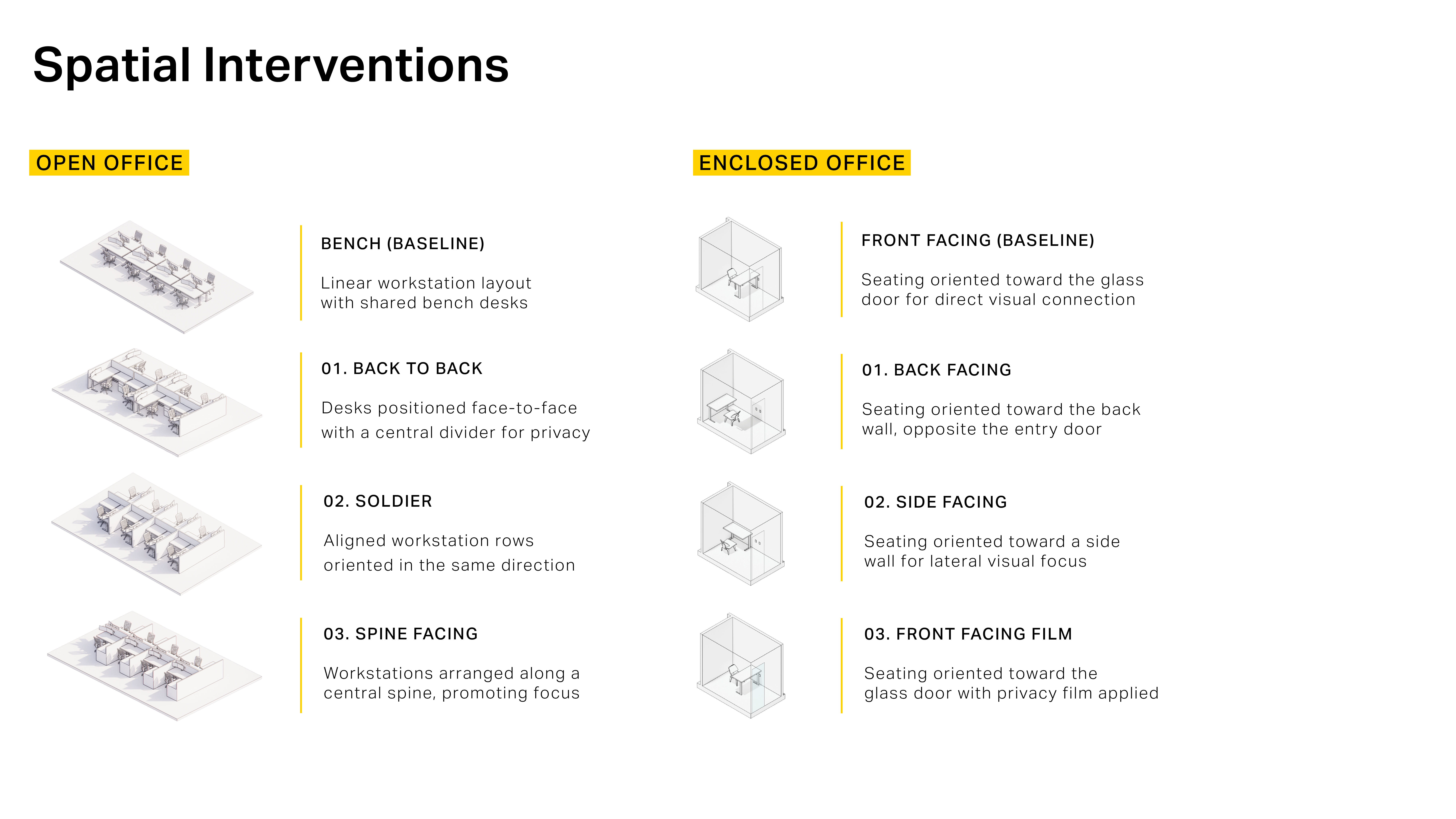

To explore how design influences focus, the team studied attention in real workplace conditions, combining behavioral, cognitive, and physiological data. Participants completed attention-based tasks in either open or enclosed controlled office settings while their brain activity and physiological response were recorded through mobile electroencephalogram (EEG) and wearable sensors.

Each session introduced variations in environmental, ergonomic, and spatial conditions to evaluate how each intervention influenced attentiveness. By combining these measurable responses with participants’ self-reported perceptions, the study provides a clearer picture of how specific design elements can shape attention. Together, these findings informed key insights on how design interventions can better support focus and wellbeing at work.

KEY INSIGHTS

Looking across all interventions, the research revealed which design strategies had the most measurable impact on attention and comfort. These results also pointed to areas where further exploration could reveal how small environmental adjustments can meaningfully influence focus.

Lighting directly influences comfort, stress, and sustained attention. It also plays an important role in maintaining healthy circadian rhythms and supporting dopamine production, particularly for neurodiverse populations, where brief exposure to bright light during the day can help regulate energy and focus.5 Participants reported feeling calmer and more focused under dimmer, indirect lighting, while bright, direct light increased distraction and eye strain. These perceptions aligned with EEG recordings showing higher sustained attention levels in diffused light conditions. The results reinforce that lighting affects more than visibility—it influences how the brain sustains attention. Layered, user-controlled lighting, such as task lamps, allows individuals to adjust brightness and tone to their task and energy level, supporting both calm and clarity.

The study found that small, intentional movement helps sustain attention, but constant motion disrupts it. The sit/stand desk was associated with improved self-reported comfort and mood. In the open office setting, it also produced a significant, measurable EEG change (a decrease in gamma power), which is interpreted as a reduction in cognitive load. This suggests that periodically shifting posture can help maintain engagement. Conversely, the footrest showed no significant EEG change in either setting. Self-reports for the footrest were mixed: some participants found it helpful for stability, while others described it as distracting or uncomfortable, particularly in the open office. This variation highlights that small movement, or fidgeting interventions are highly individual. In contrast, seating designed for continuous motion, such as yoga balls, decreased both self-reported attention and comfort.

Throughout testing, researchers also observed natural rhythmic movements such as rocking, chair adjustments, and foot tapping, that appeared to help participants regulate focus. These patterns suggest that movement acts as a form of self-regulation when it is brief and purposeful. Designing for focus means supporting movement at two scales: subtle, intentional shifts that sustain attention during work, and larger, active resets between tasks that restore it.

How much we see affects how well we focus. In the enclosed office, orientation shaped participants’ self-reported experience. Facing a side wall supported higher concentration and lower fatigue, reducing visual distractions while maintaining peripheral awareness. Although perceived as more supportive of focus, EEG data showed no statistically significant difference between any orientation. When facing the back of the office, with a glass door behind the participant, self-reported feelings of insecurity increased by 67% even as participants described higher concentration. This layout may aid short bursts of focus but was perceived as more tiring over time, reinforcing the need for spatial variety.

In the open office, spatial orientation had the strongest influence on attention across the study. The bench layout, where participants faced forward, with a wall behind them, produced a distinct EEG signature indicating significantly reduced cognitive load and stress compared to all other layouts. This balance of reduced direct visual input and activity behind, while maintaining connection, was also unintentionally provided by the acoustic hood, which helped participants minimize distraction and maintain awareness in the open office. Together, these findings demonstrate that controlled visibility—not complete isolation—can best support attention.

Attention is regulated by the full sensory mix of a space, not one stimulus alone. Sound proved difficult to control, particularly in the open office setting, where even consistent background noise remained a source of distraction. The acoustic hood intervention unintentionally combined reduced noise with limited visual exposure, helping participants sustain attention and minimize distraction in the open office environment.

The scent intervention produced the highest increase in attention but also lowered relaxation levels and increased arousal, suggesting that its stimulating effect may be best suited for more dynamic settings, such as open office environments, where a gentle boost in alertness supports focus in a more active environment. These findings underscore that sensory experience is best designed holistically. In environments where single elements cannot be fully controlled or removed, balanced layering across sound, scent, and visual conditions helps maintain focus and comfort.

Making Inclusion Actionable

The findings point to a simple reminder: focus is personal, but environments can be designed to accommodate a wide range of cognitive needs. Tunable design strategies work best when paired with a variety of space types, from quiet focus rooms to small breakout areas and informal collaboration spaces, allowing individuals to align their environment with both the way they work best and the task at hand. By identifying features proven to enhance focus and wellbeing, we can ensure they are sustained through organizational change and growth.

When design supports attention, policy and behavior ensure its success. Change-management efforts, HR practices, and daily routines all play a role in helping employees understand and use the flexible designed spaces around them. The result is a dynamic relationship between people and place, where design supports better ways to work, and workplace culture sustains design’s intent.

A More Attentive Future

This study was not focused on how individuals use control and choice but on identifying the environmental options that should be available to support it. The findings point to the value of creating adaptable settings that offer adjustable lighting, varied seating postures, and differentiated sound conditions—elements that allow employees to align their surroundings with task and comfort. Designing for attention means embedding flexibility into the workplace, giving individuals access to spaces and tools that provide them the agency to regulate stimulation, focus, and recovery throughout the day.

As task complexity changes, so should the environment - calling for design strategies that function as a kit of parts. These approaches, and the nuances of how they can be best implemented, will be explored further in our forthcoming report.

This study is only the beginning. By starting with inattentive-type ADHD, the research established a methodology that can expand to look at larger participant groups, other forms of neurodiversity and a wider range of work settings. The next phase will focus on applying the most impactful design interventions in collaboration with clients in real workplace projects to measure their impact over time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was conducted under the AIA Upjohn Research Initiative in collaboration with the University of Arkansas, with partner faculty including:

Jinoh Park, Ph.D., Assistant Professor at the University of Arkansas

Michelle Boyoung Huh, Assistant Professor at Virginia Tech

Marjan Miri, Assistant Professor at Drexel University

The research testing environment was supported by in-kind material contributions from the following:

WRG

BuzziSpace

Finelite

References

1. Staley, B. S., Robinson, L. R., Claussen, A. H., Katz, S. M., Danielson, M. L., Summers, A. D., Farr, S. L., Blumberg, S. J., & Tinker, S. C. (2024, October 10). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis, treatment, and telehealth use in adults — National Center for Health Statistics Rapid Surveys System, United States, October–November 2023. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 73(40), 891–895. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr

2. Abdelnour, E., Jansen, M. O., & Gold, J. A. (2022). ADHD diagnostic trends: Increased recognition or overdiagnosis? Missouri Medicine, 119(5), 467–473. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9616454/

3. National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Retrieved [insert retrieval date], from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd

4. Kim, J., & de Dear, R. (2013, January 7). Why open offices don’t work. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-new-office/201301/why-open-offices-dont-work

5. Bijlenga, D., Vollebregt, M. A., Kooij, J. J. S., & Arns, M. (2019). Correcting delayed circadian phase with bright light therapy predicts improvement in ADHD symptoms: A pilot study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 115, 25–31. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6423301/